all images © Nicole Franzen

all images © Nicole Franzen

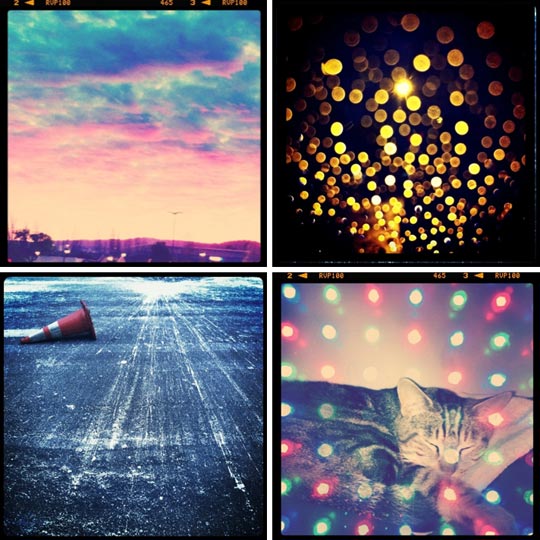

Thanks to photo apps like Instagram, and to our current culture of capture-and-overshare enthusiasm, I can no longer sit down to a meal without snapping a photo of the food. If you take a look at the various tags on Instagram related to the things that people consume throughout the day (#food #eats #noms) you'll see that I am not alone in the habitual photographing of my meals.

But outside of the realm of iPhonography, there is also a thriving professional food photography world. Yes, this is an actual job that many fortunate (and talented!) folks have managed to carve out for themselves. While some great cooking glossies have gone by the wayside (RIP Gourmet), there is no shortage of outlets for professional photographers to showcase (and cash in on) their work online and in print.

Culinary Composition

Professional food photographers may make their deliciously-staged shots look simple, but the craft of capturing food is no easy feat. Even someone well versed in the other genres of photography will have to relearn the rules when shooting subjects as fickle as couscous or cheeseburgers. And reflective subjects like glasses full of bubbly can offer significant challenges in improper lighting.

So with those sorts of challenges in mind, I've asked Brooklyn-based food photographer, Nicole Franzen, to share her tips for shooting food, including advice on equipment, lighting, styling and composition. Nicole runs the gorgeous food and lifestyle blog, La Buena Vida, and her photo clients include Bon Appétit, Edible Manhattan and Edible Brooklyn Magazines, and Gramercy Tavern, among many others.

Below are Nicole's tips on the craft of photographing food. Grab a fork and dig in!

click thumbnails to enlarge

click thumbnails to enlarge

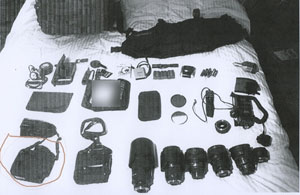

Equipment:

"You can create a great at-home studio with a low budget by using materials like foam core poster board, which comes with a reversible black/white side. This versatility is great for creating shadows or for bouncing light. Also, I use clamps from a hardware store for everything, including holding up poster boards or hanging fabrics . A tripod is an important piece of equipment. While I love free shooting, a tripod is essential for low-light conditions."

Lighting:

"I prefer to use all natural light. So for this, shooting near a window is the way to go. It's fun to play with light: draw your curtains, bounce light from above or the side, and move around. Think about how you want the food to look. Is the scene dark and moody? Bright and warm? Depending on the season, the light will change; go with it and embrace it. In winter months I shoot darker and in summer the scenes are more colorful. As a rule of thumb, it's best to shoot in the morning and late afternoon, when the light is softer. Don't be fooled into thinking that when it's sunny outside it's the best time to shoot. Cloudy days often end up creating the best lighting conditions---a natural diffuser for the sun, which creates a beautiful soft light. Shooting outside is fantastic also. Sunny days make for harsh contrast, so use a diffuser when needed."

Styling:

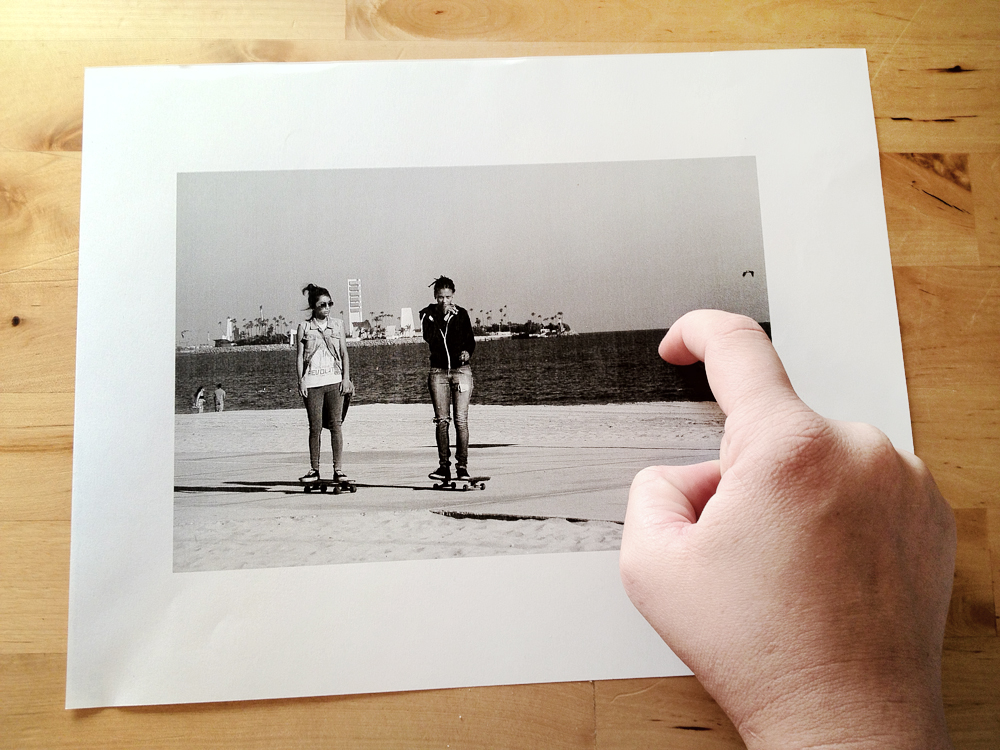

"I like to keep styling pretty simple. I think the food should be the star. I regularly frequent flea markets, second hand stores and markets, and I am always on the look out for new surfaces on which to shoot because they set the tone of the photo. I use everything from old fruit crates, which can easily be disguised as a table top, to old baking sheets, galvanized metals, distressed cutting boards and wood, and an assortment of fabrics. I use simple fabrics, linen being my favorite. You can pop into your local fabric store and pick up things like muslin, cheesecloth, burlap and other natural fibers. Even dying them yourself saves money and allows you to create they exact feel you're going for. I also recommend collecting an assortment of plates and vintage flatware to style shoots. Keep it simple overall---less is more."

Composition:

"The composition element of a photograph is really important, and I believe it's one of those things you learn from doing. For food, I often like to shoot from above. But even though this is my go-to, I still like to move around and try different angles for capturing the scene. You might try some up close, some further away. Always ask where the image is going. If it's going to be a small image for a website, try and get the food up close. If they are going to be larger images you can shoot the food from further away. In the end, all I can say is try to make it feel real, not forced."

Creating a Platform

Making beautiful photos is not all that it takes to become a working shutterbug, however. As I've shared before on DP, I'm inspired by stories like this one about London (and now New York)-based photographer, Brian Ferry, who as a result of demonstrating a clear talent for capturing dining experiences on his photo blog, The Blue Hour, was hired by Starbucks to shoot a big campaign for the brand. Similarly, Nicole Franzen created a platform for herself to show off her food photography and styling chops through La Buena Vida, and has in turn gone on to shoot foodie editorials for major publications and capture close-ups for highly respected restaurants. These two photographers have different aesthetic approaches but the one thing that unites them is that their images show a strong point of view. Nicole was, again, kind enough to share her somewhat unconventional journey to professional status and give advice on starting the journey of becoming a food photographer. Check out more of her tips below.

click thumbnails to enlarge

click thumbnails to enlarge

Training:

"I will start by saying that I had no proper training in the photography world. I am a full-fledged hands-on learner. Whenever I would try to read books about technique, the information would rarely stick. I had to learn through doing. It took years of practice and an undying love for taking photographs. It took always pushing forward and challenging myself. I feel that, as with most arts, it comes from a deep source within. Learning the technical side of things just helps you get that feeling out. Everyday I spend a large amount of time looking at things that inspire me. Whether it be another photographer's work, a stylist I envy, or mother nature. My main source of inspiration comes from nature itself. It has given us all of these beautiful things for free: texture, light, mood. It's important to take the time to appreciate that. Some of my favorite subjects to shoot are farmer's markets and rural farms. I love the organic feel of these settings and I try to represent that in my photos. For me, it's all about getting to the root of food and all the amazing people involved."

Promotion:

"The journey has been a roller coaster ride of emotions. It's not easy becoming a full time photographer, but after lots of hard work it has started to pay off. I've always had a camera in my hand and have always loved to take walks. Many of us photographers are familiar these walks and treasure them deeply. It's our time. After working my way through every genre of photography, it finally made sense that food was my true niche. I had been obsessed with food and cooking since a very young age, and so it only was a matter of time before I combined the two. The last two years I have spent all of my time devoted to learning about photographing food. I started a blog, which was my initial way of introducing my work to the world. I started by photographing my own meals. It then continued to grow and grow. I've met almost every client I have through the internet and referrals. Get to know everyone in the industry and build relationships. Be persistent and consistent. Social media has helped us photographers a lot---embrace that. You will be surprised when the emails start to come in."

Business:

"Running a small photography business has its challenges. I am constantly learning as I go. I've become a jack of all trades---not only are you doing the photography, you are doing book keeping, invoicing, and all the other details that are involved in running a small business. I make mistakes, and then I learn from them. Every day I feel blessed that I am able to do what I love. I was never destined for a desk job. The best thing about photography is that it's always changing: new clients, new experiences and new shoots. My only words of advice are follow your heart, keep on working hard and always challenge yourself to get better."

Tools:

Nicole primarily shoots with a Canon 5D Mark II and edits in both Aperture and Photoshop.

Visit nicolefranzen.com to view more inspiring images. Thank you, Nicole!

photo: Jamie Beck / From Me To You

photo: Jamie Beck / From Me To You

click images to enlarge

This illumination is usually found during the middle of the day, and can produce some very harsh light. On the plus side, sunlight from above often casts an even illumination across the top of your subject and may bring out its color. On the flip side, however, this lighting may appear flat and creates harsh shadows on people’s faces. You’re better off moving your subject to a shady spot, or if this isn’t possible, use your camera’s flash to fill in the shadows.

click images to enlarge

This illumination is usually found during the middle of the day, and can produce some very harsh light. On the plus side, sunlight from above often casts an even illumination across the top of your subject and may bring out its color. On the flip side, however, this lighting may appear flat and creates harsh shadows on people’s faces. You’re better off moving your subject to a shady spot, or if this isn’t possible, use your camera’s flash to fill in the shadows.